26 Sep How Localisation and Resilient Design Fueled the Success of Climate Smart Agriculture Programmes in Uganda’s Refugee Response – Insights from the Northern Uganda Resilience Initiative (NURI)

In recent years, Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) has emerged as a game-changer, helping to foster resilient farming practices and bolstering food security in Uganda.

What is Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA)?

CSA is defined as “an integrated approach to managing landscapes—cropland, livestock, forests and fisheries – that addresses the interlinked challenges of food security and climate change.”[1] It focuses on enhancing productivity and building resilience by improving farmers’ knowledge of climate-smart production methods.

CSA in Uganda

Uganda is heavily reliant on agriculture; the sector employs over 80% of the population, but because agriculture is predominantly rain-fed, it is vulnerable to climate-related stresses. Rising temperatures and more frequent extreme weather conditions have led to decreased food security, water scarcity, and ecosystem degradation. Despite being aware of these challenges, smallholder farmers in Uganda have limited access to information on managing climate-related stresses.[2]

Uganda follows a settlement-based model, where refugees receive 30 x 30 metre plots of land to build homes, grow crops, and become part of the local communities. This approach is designed to decrease reliance on aid, and promote peaceful coexistence between refugees and host communities. However, refugee communities often lack guidance and training in efficient farming techniques. In the face of dwindling aid and shrinking food rations in Uganda’s refugee response, more and more humanitarian response organisations are incorporating CSA into their programming to help refugee-hosting communities achieve self-reliance.

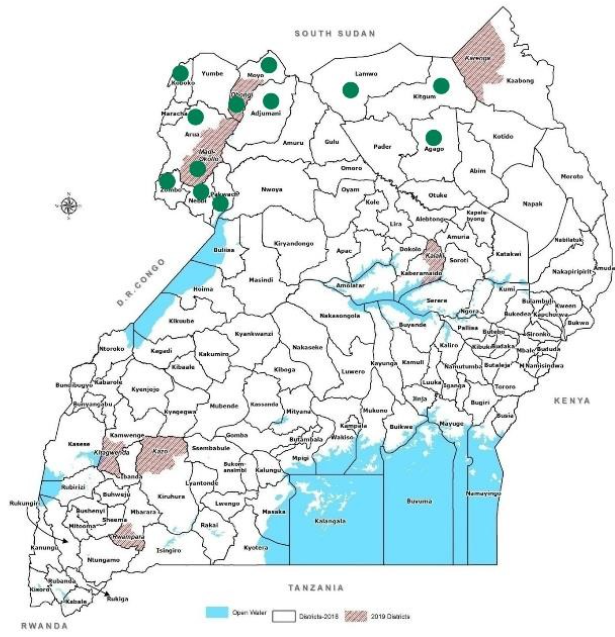

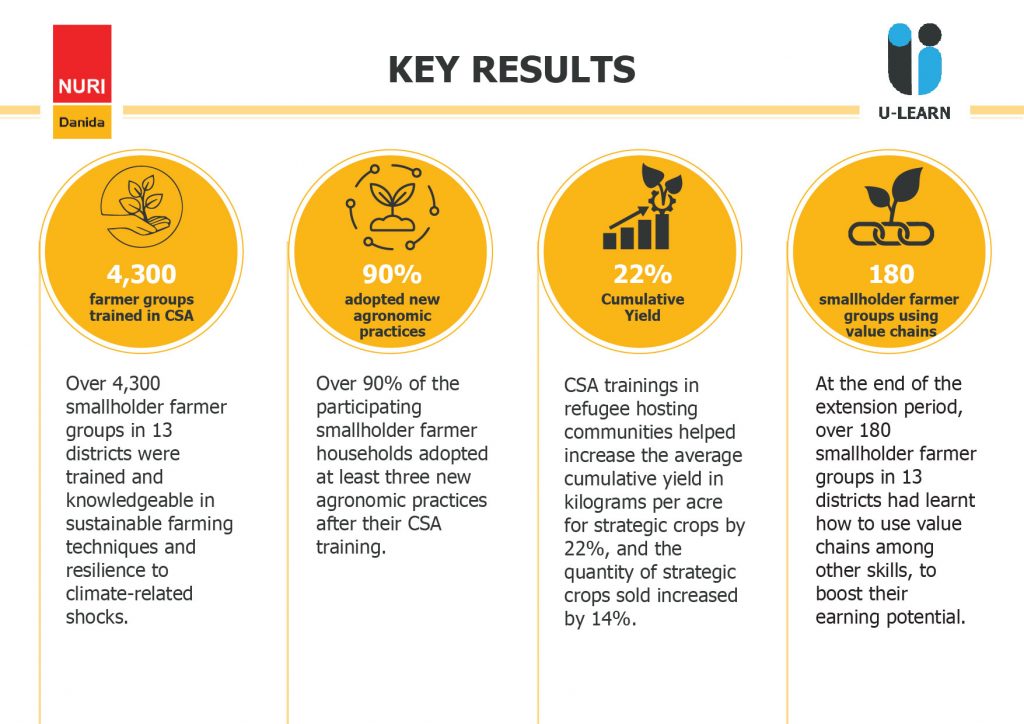

Whether or not CSA is successful really depends on how it is implemented. For example, one of Uganda’s refugee response donors, the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, recently achieved impressive results by incorporating localisation and resilient design in their CSA programmes during their Northern Uganda Resilience Initiative (NURI) that ran from 2019 to 2023. NURI was dedicated to enhancing the resilience and equitable economic development of refugees and refugee-hosting areas in Northern Uganda and CSA was one of its core pillars. By the end of the four-year period, over 4,300 smallholder farmer groups in 13 districts were trained and knowledgeable in sustainable farming techniques and resilience to climate-related shocks.[3]

How NURI used localisation and resilient design to achieve success in CSA

1. Localisation: Close collaboration with local stakeholders cascaded the adoption of CSA practices amongst smallholder farmers

The NURI team employed their version of a ‘bottom-up’ approach by closely and regularly consulting with participating smallholder farmers and involving key local partners such as the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the National Agriculture Research Organisation (NARO), District Local Governments (DLGs) and Lower Local Governments (LLGs) in planning and implementation.[4] This localisation strategy worked well; according to NURI programme reports, 93% of the participating smallholder farmer households adopted at least three new agronomic practices after their CSA training.

Joseph Ebinu, NURI’s acting Programme Management Advisor, explained how the localisation component helped achieving success: “The bottom-up approach worked very well because it addressed the farmers’ needs exactly. By the time implementation started, it was what the stakeholders were expecting. Budget lines and stakeholder roles and responsibilities were very clear, so there was buy-in from the beginning. NURI held regular consultative meetings with OPM and other partners to address challenges. Extension staff and local government stakeholders were provided with capacity building using relevant locally-based knowledge partners. We also held annual stakeholder meetings at the national level, including relevant ministries, development partners, [Denmark] embassy, and DLGs, which served as accountability for the year.”

DLGs played a central role in cascading the use of CSA practices to smallholder farmers. Dr. Dratele Christopher, Moyo District Production Officer, shared that DLGs supervised the NURI team and provided technical backstopping. This ensured that CSA programming was effectively integrated into DLG agriculture extension services and could be continued even after the project timeline. As of 2024, smallholder farmer groups that participated in NURI’s CSA trainings are still getting agriculture extension services from their respective DLGs.

NURI also hired refugees and host community members as extension staff. Joel Bayo, a Climate Smart Agriculture Coordinator, highlighted the importance of hiring locally: “They [staff] understood the language, culture and community behaviour, so they knew how to manoeuvre. They played a crucial role in providing training, facilitating communication, and ensuring the programme’s relevance to the local context.”

Through its localised and collaborative approach, NURI fostered the widespread uptake of CSA practices, laying a foundation for long-term climate resilience and sustainability in Northern Uganda refugee-hosting communities.

2. Resilient design: NURI set up their CSA programmes for success beyond the project scope.

NURI’s programmes, including CSA, were tactfully designed with the intention to have them succeed beyond the four-year project scope. Resilient design in NURI’s CSA programmes constituted four main components: i)the selection of viable crop species, ii)flexibility to support innovation, iii)linking CSA with other NURI pillars and iv)focusing on empowerment and knowledge transfer.

a) Selecting viable crop species enabled continuous cultivation by smallholder farmers.

To choose the most suitable crop species, NURI, in collaboration with DLG agriculture extension staff, conducted a comprehensive assessment considering various factors, such as a crop’s potential to thrive in specific locations, market availability, participating farmers’ knowledge of the crop, and its suitability to the area’s agroecology. To ensure the viability of the selected crop species, the extension staff established learning and seed multiplication sites. These sites served as testing grounds where the growth and adaptability of the chosen crop species were closely monitored before distribution to farmers. Farmers made informed decisions on the types of crop species they wanted to cultivate based on the knowledge they obtained on crop yield quantities and average prices. The extension staff also trained farmers in intercropping, timely land preparation, the cultivation of drought tolerant, fast-maturing and pest/disease resistant varieties, soil and water conservation and post-harvest handling and marketing of selected strategic crops.

NURI’s meticulous selection process of viable crop species enabled smallholder farmers to grow crops well-suited to their local environment and, as such, promoted sustainable agriculture practices and technologies.

b) NURI’s CSA programmes allowed for flexibility to support innovation.

According to Joel Bayo (CSA Coordinator) flexibility was one of the most outstanding features of NURI’s CSA programmes. Bayo shared that when CSA activities began, NURI had a well-established curriculum. But during implementation, some changes were made to align with contextual realities. An example of CSA curriculum adjustment was the adoption of the farmer-to-farmer extension. When the agriculture extension staff’s ability to reach every farmer proved difficult, a few members of each farmer group received hands-on mentorship in tree management practices and were tasked to cascade the skills to fellow farmers, with the extension staff only providing support in case of gaps. The approach resulted in increased outreach of extension services, uptake and the sustained survival of tree species.[5]

c) Linking CSA with the other NURI pillars and integrating the use of Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLAs) improved farming outcomes.

NURI linked CSA with two other pillars – water resources management (WRM) and rural infrastructure development. Solomon Osakan, an OPM Refugee Desk Officer, shared that infrastructure development, such as road and bridge construction, shortened the distance from farms to markets, making it easier for farmers to transport and sell their produce. Incorporating WRM through establishing eight micro-catchments in four refugee settlements increased water availability and crop yields amidst climate-related stresses such as prolonged drought. These micro-catchments included food forests near water points, protected springs, soil and water conservation structures and water ponds. However, the long-term impact and sustainability of micro-catchments was not extensively explored under NURI. It would be interesting to see how they perform in the long run.

NURI’s CSA programming also integrated the use of Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs); households obtained loans from VSLAs to finance the purchase of various agricultural inputs including seedlings and execute requisite farming activities in a timely manner (in-season).

Timely crop cultivation and better access to markets increased crop yields, significantly improving household incomes and ultimately, piquing the interest of other smallholder farmers in CSA practices.

d) A focus on empowerment and knowledge transfer left a lasting positive outlook on CSA.

Finally, NURI’s CSA programmes focused on empowerment and knowledge transfer rather than providing handouts. For instance, in 2023, NURI introduced household-level tree growing to interested CSA farmer groups. Tree-growing was implemented through a cost-sharing model where individual farmers/households paid 30% and the programme paid 70% of the costs of tree seedlings. Farmers paid for seedlings of their choice in quantities they could absorb.[6]

Additionally, smallholder farmers received training in groups and through farmer-to-farmer extension methods. According to Dr. Dratele, the low ratio of extension staff to farmer groups facilitated in-depth knowledge transfer.

Youtube Chandiga, a Ugandan CSA smallholder farmer trainee, shared his experience: “They trained us [on] how to do everything- how to maintain seeds, market and many other things. This year, [2024], I increased the acres I’m planting. The food is plentiful. Some is for eating, some is for selling. Before training, the produce was not as much. Now I know very well what to do and I’m able to train other farmers and help them understand how to do it.”

Chandiga’s sentiments are shared by several other smallholder farmers who received CSA trainings. Their homes are much more food secure than before and they are much more confident about getting good yields and as such, have increased their farming acreage. Because of this, not only have they enthusiastically carried on with the CSA practices, but they are also willing and able to train other smallholder farmers to improve their lives.

Dependency mindset and water access challenges in CSA

NURI’s CSA programmes were met with several challenges, chief among them being a dependency mindset in Uganda’s refugee response and a lack of access to water for agriculture.

According to Joel Bayo, heavy reliance on handouts in refugee-hosting areas led to an expectation that NURI would provide everything, including a market for produce from CSA trainings. Realising the need for a mindset shift to sustain CSA beyond the four-year project scope, NURI had a one-year extension from 2022 to 2023. During this time, several activities were implemented, including the continuation of participatory farmer market schools that had started the previous year. Farmer market schools were established to help smallholder farmers learn to independently explore markets and identify opportunities.[7]

At the end of the extension period, over 180 smallholder farmer groups in 13 districts had learnt how to use value chains among other skills, to boost their earning potential.[8] It’s too early to tell whether the skills can be sustained through shifting economic trends and climate-related stresses or if they are transferable in the long run.

Another major challenge pointed out by DLG officials and NURI team members was a lack of access to water for agriculture in several refugee-hosting areas. These areas face over-exploitation of forest resources, degradation of wetlands and an absence of integrated water resources management plans, resulting in dwindling underground water resources. NURI implemented WRM in some settlements which helped increase water availability in the immediate term. However, it’s not clear how effective this will be in the long run. For instance, by the end of the NURI extension period, less than 21% of the food forests established were being maintained, indicating a low likelihood of survival. Additionally, rural point water source operation and maintenance (O&M) is a major challenge in Uganda.

A DLG staff suggested exploring other solutions, such as valley dams, to increase access to water for agriculture in refugee-hosting areas.

Conclusion

Despite the challenges, NURI’s localised approach and resilient design in CSA programming left a positive and lasting impact on the refugee response in Northern Uganda. It’s been one year since NURI wrapped up, but CSA training participants are still reaping the benefits of its transformative impact.

Vicky Night, one of the refugee women who participated in CSA trainings, said:

“The knowledge I got from NURI really helped me. They gave us improved farming practices that we didn’t know before. The vegetables I planted during the training, I sold them, got some chickens and ducks and they have multiplied. Before, we didn’t know how to grow vegetables. We would plant and get nothing. They would die because we didn’t know how to make local pesticides. My children didn’t have school fees and sometimes, they would sit at home, but now I make money to pay and I took them to better schools. Right now, I’m preparing to plant more vegetables.”

Vicky Night is just one of many CSA training participants who boast of increased crop production, the continued use of sustainable farming techniques, and better resilience to climate change-related stresses beyond the NURI scope. In four years, CSA trainings in refugee hosting communities helped increase the average cumulative yield in kilograms per acre for strategic crops by 22%, and the quantity of strategic crops sold increased by 14%.

For more information about NURI’s approach to Climate-Smart Agriculture, visit their website here and read more lessons learnt here.

References

[1] World Bank Group, Climate Smart Agriculture, last updated 26 February 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climate-smart-agriculture

[2] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Enabling Farmers to Adapt to Climate Change | Uganda, https://unfccc.int/climate-action/momentum-for-change/ict-solutions/enabling-farmers-to-adapt-to-climate-change

[3] NURI, Climate Smart Agriculture, https://nuri.ag/projects/climate-smart-agriculture/

[4] NURI, Greening Our Environment Through Household Tree Growing in Northern Uganda, https://usercontent.one/wp/nuri.ag/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/NURI-Greening-Environment-v4.pdf

[5] NURI, Greening Our Environment Through Household Tree Growing in Northern Uganda

[6] NURI, Greening Our Environment Through Household Tree Growing in Northern Uganda

[7] NURI, Greening Our Environment Through Household Tree Growing in Northern Uganda

[8] NURI, End of NURI extension report, 2023, https://usercontent.one/wp/nuri.ag/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/End-of-NURI-Extension-2023-Final-Report.pdf